Client Alerts

Fair Is Fair? Oral Argument in Warhol v. Goldsmith

October 2022

Client Alerts

Fair Is Fair? Oral Argument in Warhol v. Goldsmith

October 2022

On October 12, 2022, the United States Supreme Court heard oral argument in the case The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith and Lynn Goldsmith, Ltd. This case involves the question of what constitutes fair use under copyright law. Specifically, the issue is whether Andy Warhol’s painting of the musical artist Prince, based on a photograph by Goldsmith, was sufficiently “transformative” to meet the first prong of the four-part fair use inquiry.

Background

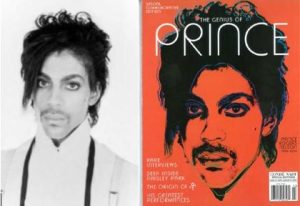

The source material at issue is a 1981 photograph of Prince taken by Goldsmith. In 1984, using that photo as a starting point, Warhol created a series of silkscreen paintings, two screen prints on paper, and two drawings, referred to collectively as the “Prince Series.” One image from the series originally appeared in Vanity Fair in 1984. After Prince’s death in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company, Condé Nast, published a different image from the Prince series (“Orange Prince”). The photo and magazine cover are depicted below:

After Goldsmith learned of this use, she contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation, alleging infringement. The Foundation filed an action for declaratory judgment of noninfringement, and Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement, based solely on the Condé Nast Orange Prince magazine cover. The District Court granted summary judgment in favor of the Foundation, finding that the entire Prince Series (and thus Orange Prince) was fair use. The Second Circuit reversed, finding among other things that courts are not “art critics” and should not take it upon themselves to discern what message or meaning a work intends to convey.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari to resolve the question of whether a work is transformative when it conveys a different meaning or message from its source material, or whether a court is forbidden from considering the meaning of the accused work when it recognizably derives from the source material. The actual argument was much more far-reaching than the formulation of the question presented would suggest.

Summary of Oral Argument

Roman Martinez argued on behalf of the Foundation; Goldsmith was represented at the oral argument by Lisa Blatt. In a sign of how important this issue is, the United States Government requested and was granted leave to argue, as well. Siding with Goldsmith, the U.S. Government was represented by Yaira Dubin, Assistant to the Solicitor General.

The Court was active in its questioning, with the first questions posed to Mr. Martinez and Ms. Blatt coming from Justice Thomas. Nearly every justice expressed skepticism of, if not hostility toward, the Foundation’s position. The Foundation focused on whether a follow-on work conveyed a different meaning or message from the source material, which the Justices appeared to find an overly broad and vague standard. Justice Jackson told Mr. Martinez that he was conflating “meaning and message” with “purpose and character,” the latter of which is contained within the fair use provision of the Copyright Act itself. Justice Barrett was concerned that the suggested test would make it difficult for any work to be deemed derivative as opposed to transformative. She told Mr. Martinez that every time he was presented with a difficult hypothetical that tested the limits of his argument, he would “flip to Factor 4” of the fair use test, which looks to whether the works compete in the same market. Justice Alito was concerned about how to prove the “meaning or message” of a work. Would it require expert testimony from art critics? Testimony from the artist? Mr. Martinez stated that, as in any case, evidence could take many forms, including the views of the Court as well as expert and artist testimony. He emphasized that under the meaning or message test in the earlier Supreme Court case Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, courts aren’t required to decide what the meaning or message is, but rather whether any different meaning or message could be “reasonably perceived” by the public. Justices Sotomayor and Kavanagh both emphasized that the actual purpose of the two works is the same, because each was created for the commercial purpose of being published in magazines.

The Justices questioned Ms. Blatt and Ms. Dubin extensively as well, apparently trying to find some way to determine how to protect an artist’s exclusive right to his or her derivative uses while still leaving fair use as a viable doctrine. Justice Sotomayor asked Ms. Blatt about the fact that the Second Circuit “ignored” Campbell’s meaning or message test altogether, a point that Ms. Blatt vehemently disputed. Ms. Blatt stated that the Second Circuit considered that issue relevant as part of its overall analysis in which it found the Warhol piece non-transformative. Justice Alito asked about the “art critic” line in the Second Circuit opinion. Ms. Blatt responded that the Second Circuit simply meant that courts should not engage in a subjective test as to what “vibe” is created by a work, and instead should focus objectively on the purpose and character of the work. She focused on the commercial nature of both. Justice Barrett asked if the result would be different if the purpose of the Warhol piece was to hang in a museum instead of being published in a magazine. Ms. Blatt herself invoked Factor 4, focusing on the fact that the works in that situation would not compete. Justice Kagan asked whether, if the purpose of the Copyright Act is to foster creativity, Factor 1 should ask whether the new work added significant creativity. Ms. Blatt answered that the amount of creativity isn’t the right analysis, because derivative works can themselves be highly creative.

Ms. Dubin picked up that thread, emphasizing repeatedly that the test for fair use shouldn’t be whether the new work was creative, because derivative works by an artist often involve a great deal of creativity. She agreed with Justice Jackson’s suggestion that the first fair use factor asks, “Why are you using my work?” Justice Jackson stated the view that there must be a different purpose for that use, not just a different meaning or message. Justices Kavanagh and Kagan pressed Ms. Dubin to explain her proposed test. She said that the source material needed to be “necessary or at least useful” to the creation of the follow-on work. Andy Warhol did not need the Goldsmith photo to create his work. He could have used another photo, licensed the image, or simply taken a photo himself. As a result, the work was not transformative.

The oral argument ran much longer than scheduled, attributable primarily to the Court’s continued questioning of Mr. Martinez long after his allotted time had expired. By the time Mr. Martinez offered his rebuttal to Ms. Blatt and Ms. Dubin, the Justices were apparently out of questions: They did not ask a single one.

Brief Analysis

Even though the Supreme Court itself employed the “message or meaning” approach in Campbell, it seems clear that the Court as currently constituted is looking for a different test for whether a work has a different purpose and character from source material. The Justices did not necessarily seem satisfied with the Second Circuit’s analysis either, or with the tests proposed by Goldsmith and by the Government. Justice Jackson raised the prospect of whether the matter should just be remanded, because regardless of what test is selected for Factor 1, the parties had not briefed or argued the other factors that must be considered as well.

Predicting the outcome of decisions based on oral argument is risky, but it certainly appears as though Goldsmith will prevail, possibly in a 9-0 decision. The primary questions now appear to be the breadth of the upcoming opinion, and whether the Court simply sends the case back to a lower court instead of making a final pronouncement as to whether the Warhol work was fair use. We should find out in the next few months. In the meantime, as always, anyone wanting to use copyrighted material to create a new work – even one that might be considered “transformational” – would be wise to obtain legal advice before doing so.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

For more information, please contact:

- Brian K. Brookey | 202.505.6473 | brian.brookey@tuckerellis.com

This Client Alert has been prepared by Tucker Ellis LLP for the use of our clients. Although prepared by professionals, it should not be used as a substitute for legal counseling in specific situations. Readers should not act upon the information contained herein without professional guidance.